What I Did on My Summer Vacation

Published on Tue, Sep 10, 1985

By: Len Frank

“March 15, 1985: Kenny K. has asked me to race his Alfa Giulietta Sprint Veloce at the Monterey Historics in August. Naturally I say yes…” – Len Frank

Inset photography by David Gooley

March 15, 1985: Kenny K. has asked me to race his Alfa Giulietta Sprint Veloce at the Monterey Historics in August. Naturally I say yes. I have a friend who says I’m a Car Slut—I’ll go anywhere to race anything. Car Sluts are easy.

Kenny K. was a friend of a friend and now he’s just a friend, my original friend having long since stopped talking to Kenny.

I suspect this has happened to Kenny before—getting a friend, losing a friend. He can be engaging. He can be kind of frustrating.

I’ll rephrase that: “infuriating” might be a more apt description, “intractable” might work for his lighter moments.

Kenny can do anything with his hands, make anything, a superb craftsman. He also has a wonderfully developed sense of aesthetics that becomes supremely important to him at all the wrong times. See “infuriating” and “intractable” above.

Kenny is a model maker—he makes prototypes for industrial designers—models of computers and kitchen gadgets, imitations of metal objects and injection molded plastic things. When finished they are as close to perfect as a man-made object can be. Sometimes they get finished on time. Sometimes they get finished late—very, very, late. Sometimes they don’t get finished at all. Two out of three.

Most of Kenny’s clients live in Los Angeles. When I met him he lived in his workshop in Santa Fe, in New Mexico, up in the mountains, where his clients couldn’t easily get their hands around his throat.

April 1, 1985: I am entering into one of my broke periods. Writing is one of the better things that I have done to make a living but financial security is not a big part of the benefit package. Write a story and three months later, get paid for it. Maybe six months later. Maybe never. Things could be worse. Louie the Landlord is understanding. I have cars to drive. I have a “ride” for Monterey. Things could be a lot worse.

Kenny calls me. The car is swell, ready to go except for a little crossmember that supports the transmission. It had been replaced by an angle iron substitute before Kenny bought the car. How long ago was that? About ten years. It works, but he hates the way it looks. Find him the crossmember.

But he is excited about the race, about Alfa being the honored marque—looking forward, etc.

April 5, 9, 17. Kenny wants reassurance. Will the race be too hard on the car? What are the chances of my rolling it up into a big red ball? Will I wear the tires out? He would install the 1600 Veloce engine that he has if he had not already sold it and the Spider that it is installed in to the (ex-)friend who introduced us.

I reassure him. I’ll get tires (somehow). I’m the model of restraint—Alfa Giulietta Sprint Velocevintage racing isn’t really racing, I’ll drive the car within the strict limits set up by the engine builder (Dave Vegher, one of the best engine builders I know, winner of three SCCA national championships in a Lotus Elan. Vegher has no limits so I’m OK there.). I’m sure I tell other lies as well.

April 30. I have wandered from Alfa dealership to Alfa dealership looking for the little crossmember. Most Alfa dealers don’t remember Giuliettas, and why should they? LA is fortunate in having lots of independent Alfa shops and one big independent Alfa parts warehouse (Alfa Ricambi—they not only stock Alfa stuff, they reproduce bunches of older parts). Still no luck on the crossmember. It’s a part that never breaks, never wears out, so why would anyone save it.

May 15. More reassuring phone calls to Kenny K. in the preceding two weeks. Los Angeles has an Alfa-only wrecking yard (then Alfa Recycler, now Alfa Pacific) and I had called them first looking for the elusive crossmember:”nope—don’t have one,” but by now I’m beginning to walk around the backs of Alfa shops and dealerships to commune with the scrap piles. And there, on my return, in back of Recycler, is a broken tranny case with the crossmember attached. “Take it.” I send it off express so that Kenny can install it right away. Express costs me fifteen bucks.

That emergency is over just in time—”broke” is turning to “destitute”. Driving around LA is only slightly more expensive than phoning around. My phone is in jeopardy. Now I have to concentrate on hitting my friends up for tires, for a competition harness, for all of the other paraphernalia and labor that it takes to make the car legal and race worthy.

May 19. Contact friends with BFG Racing press relations. Nice people, really helpful. “Yeah, I think we can supply you with a set of tires—what size?”

I tell him that the car originally had 155X15 but a 185-70 would probably do the job. “185-70…” there is a question in his voice, “I don’t think anybody makes anything like that in high performance tires—we sure don’t. How about 195-60, or better, 205-50…?” Another euphemism for vintage is, of course, obsolete.

May 30. Can’t get any kind of answer from Pirelli–they appear to have given up on LA.

June 3. Kenny K. calls again. I ask him if the crossmember works. He’s kind of vague, says that he hasn’t really tried it yet but he will soon. He’s trying to get a project out for one of his clients–it’s about three months overdue; he’s working on one of his other Alfas (he has the Sprint that I’m going to—I hope—race, a 1964 Giulia Spider Veloce that he has sold and must be fully restored—see “friend-of-a-friend” above—he has a pair of rare, old 1750s, a ’30 and a ’33, both custom bodied, both dismantled); he’s talking a little wistfully about a model airplane that he still has that he started when he was 15—he’s now in his fifties—that he would certainly like to finish and fly while the weather is still good; his million-mile Volvo daily driver is acting up…there are many, many other topics.

June 16. I’ve tried Goodyear and Firestone with no luck. Goodyear makes real racing tires in vintage sizes in some obscure plant—they are definitely not giving them away. Ditto Avon. Ditto Dunlop.

June 25. I’ve read everything that I can about Alfa wheels. No matter how I add, subtract, convert from metric to English and back again, rim width keeps coming out five inches maximum. Four-and-a-half seems to have been standard. But I find some obscure reference to different wheels on the exotic Sprint Zagato. In 1985 an SZ is worth over fifty grand. Like nearly all vintage cars, the sum of the parts is a lot more than the car as a whole. Yet, I find a friend who is hoarding a set of early Veloce/SZ wheels against the time his car is restored. He will consider letting me use them.

July 2. I am invited to a Fourth of July barbecue by the wheel owner. He lives sixty-plus miles away. Isn’t southern California wonderful. Talk to Kenny K. He hasn’t installed the crossmember yet but we have a nice discussion about his model airplane.

July 4. Of course there was traffic all of the way to the barbecue, why did you ask. Barbecues are a modern tribal ritual and I’m not a member of the tribe. What with helping to pick up the beer keg, starting the charcoal, talking to a bunch of people who all want to hear me say that racing is dangerous and that I’m crazy for doing it, or, talking to a bunch of people who are telling me that I have The Life, it’s time for the fireworks before I have seen the wheels. I have never liked fireworks, I never went aaah when the grand finale was set off.

The wheels, their owner is telling me (about 11pm), are bi-metallic—steel centers, alloy rims riveted together. Light, rare, very expensive. He’s telling me that they have been painted several times prior to his buying them and would I mind stripping them and repainting… we are plowing through all of the garage clutter to the wheels which are stored in the back on the bottom behind and under everything. There is a law of nature lurking in this inevitable arrangement.

We finally get to the wheels and have to pass them out, hand to hand, over the garage effluvia. No, I don’t want another beer.

My friend is scraping away with a penknife, showing me how many layers of paint have been built up since the wheels left Borrani in 1956. Scrape(red), scrape(black), scrape(silver), scrape(red again), scrape—off comes the domed head of a rivet. Pause. He tries another one with the same result. A little rust? A little electrolysis? Maybe I could re-rivet them before I strip and repaint them. I measure the rim width. Four inches. There was traffic on the way home.

July 7. Call Michelin. Sure. Maybe a set of MXVs, 185-70—not really racing tires. By this time I no longer care. They will start the paperwork, I can pick them up at their warehouse in remote LA. Soon. Maybe a week, maybe ten days. I settle for a set of regular five inch wheels graciously offered.

July 12. I am listening to Philippe. Morse has prevailed upon him. Philippe is telling me that the driver’s suit he is giving me is triple layer but that it has a higher rating than everybody else’s four layer suits. I have never seen a four layer suit. But he is giving me a suit! I love him, I love the handful of decals he makes me promise to put all over Kenny’s car. He is giving me a harness. Giving me! He is telling me that these Sabelts are exactly the same as those used personally by Alain. I am exactly twice as big as Alain (except for the nose). Vive la France.

July 14. Down to the last $200 between me and absolutely being without funds. I must be insane to even consider going racing. Never mind—I’m going. Morse comes through again, says that he will put up the entry fee, says that it’s cheaper than buying pit passes and paddock parking.

July 17. I don’t have a place to stay in Monterey. I don’t have tires for the car. I don’t have the car. The tires have to be shaved, engine oil changed, new filter added, maybe an exhaust megaphone (just for the noise), the wheels have to be stripped and painted, the car tuned, drain plugs wired, valves adjusted, catch bottles fitted. I start to make out lists of things to be done, lists of items to get, lists of people to call, lists of lists.

I have never seen the car. All I have is Kenny’s word that all is well. Kenny is meditating. Kenny is model building. Kenny has not yet installed the crossmember.

July 20. The paperwork from Michelin arrives.

July 21. I’m at Michelin’s warehouse at 8am. It opens at 9. They give me the tires. No one seems to be very interested in what I’m going to be doing with them.

Over to Doug’s body shop with the tires and wheels. He has a tire truing machine, an old tire mounting machine, a wheel balancer. I don’t even know whether the 185-70s will fit Kenny’s Alfa. Doug wants to go to lunch. We sit in Marie Callendar’s, I eat, he mostly smokes and blows smoke in my face. I don’t care—he has a tire truer, wheel balancer, etc. Car Slut.

Doug has the wheels painted while we’re out. He’s trying to sell me on his latest scheme. He’s a charter member of The Scheme of the Month Club, a real wheeler and dealer. He has a good, profitable body shop but it’s never enough. The tires are in the drying oven when we return–wait a long hour for them to cool.

Back to work: first I check out the wheels. Round to within a thou or two. I don’t know what I would have done if they weren’t. Then I ask Doug to show me how to use the tire mounting stuff. I haven’t mounted a tire in twenty years. Doug tells me to take it to the tire store where he does business and let them mount it for me. Why do I get stubborn at times like this? “I’ll do it, I’ll do it.”

After an hour of struggling I finally get the routine down. The last tire only takes me twenty minutes to mount.

Have you ever shaved a tire? God, I hope not. I suspect that people who shave tires have shorter lives than asbestos workers who mine coal as a hobby. The real purpose of a tire truing machine is to make a tire more concentric with its wheel center. Shaving a tire with it is a little like rubbing your head and patting your stomach at the same time. So using a tire truer to

shave a tire is a lot like, well, using a tire truer to shave a tire. A tire truer arcs across the face of the tread while the tire rotates—which is exactly the opposite of what is wanted. The idea is to make the tread area flatter (instead of arced), the tread shallower so that the rubber doesn’t squeegee around, so that as much rubber is on the ground as possible. One hand turns a knob that moves the blade in, controls the depth, the other knob changes the radius of the cutting arc, controls the contour, another the speed control.

With enough practice it will work, but the catch is the air (and lungs and eyes) gets so filled with rubber dust that no one will ever live long enough to get really good at it. Still, there’s- no pun–a learning curve. It wasn’t too hard to tell which tire I did first, which last. I sneezed and coughed rubber dust for weeks. Racing is dangerous.

July 24. The race is less than a month away. I call Kenny. He’s playing with his parrot. All during the phone call he divides his attention between the bird and me. If I understand him correctly he will have the crossmember installed as soon as he overhauls his floor jack. Give him a week. He keeps interrupting the conversation with me to have one with his parrot.

But we talk about a 5.12 rear end (it has a 4.55—he thinks), about re-degreeing the cams (Alfas have vernier-style cam gears that allow centers to be changed), about lowering the car (where will we get springs, will it clear the tires), how are the brakes (fine), how are the shocks (Konis), how tight are the suspension bushings (squawk).

July 25. I make airline reservations, pay in cash. I have $28 left. Then I go home and then call Kenny. “I’m going to be there on August second. Meet me in Albuquerque.”

He is very agreeable, sunny even. Just before I hang up he mutters something about fixing the Volvo so he can come get me. I don’t want to know about this. My phone bill is tragically overdue, the phone company is threatening me, jeopardy is everywhere.

For the next few days I twitch around, call friends who have shops and plead for help. Everyone says yes.

August 3. Kenny is there at the airport with his tired green Volvo wagon, waiting. He’s positively bubbling over. I had explained my financial condition on the phone and he’s anxious

to buy me lunch. I’m insistent about going to see the Alfa first. We drive up into the mountains, up the long road to Santa Fe. He tells me about the weather, about the number of cops on this, the busiest north/south road in New Mexico, the entire history of the Volvo, his relationship with his parrot, all of the cute things it does and says.

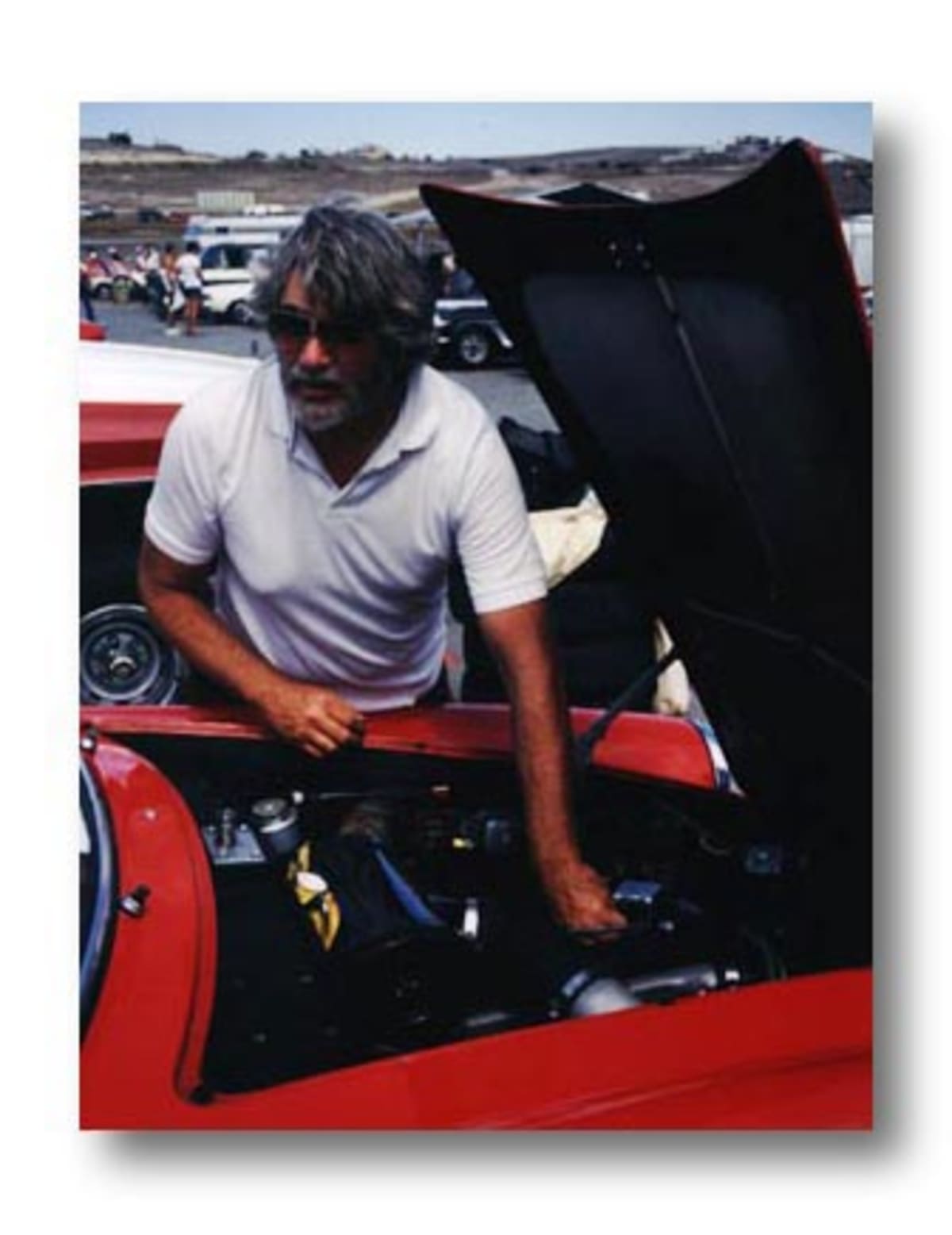

Kenny’s shop has a Santa Fe adobe facade. He parks the Volvo inside. The shop is big, clean, well arranged. There in the loft is the world’s longest running model airplane project. There are the two dismantled Alfa 1750s, at one end, the furniture he lives on, the shower fifty feet away at the other end. Next to the furniture, the famous parrot in its own private tree.

And in the middle, like a set piece, the Sprint Veloce, clean, red, very pretty. “Is the crossmember in?”

About this time the parrot climbs down from the tree and waddles across the floor to meet me–he starts to climb up my leg. It hurts. Kenny plucks him off and talks to him in the manner of a doting aunt chuking her favorite nephew under the chin, cooing.

“What about the crossmember?”

“Maybe you’d like to take a shower,” says Kenny, “before we go to lunch.”

I’m defeated. I’ll take a shower. “Great,” says Kenny, “I’ll finish overhauling the jack while you’re in there.” I’m sure the hollow feeling in my chest has something to do with the altitude.

Kenny is sitting on the floor assembling the jack when I come out. I wander around looking at things—it’s a beautiful shop and he does amazing work. He has a row of machine tools along one wall—drill press, two lathes, a couple of milling machines…one of which is the best looking milling machine I have ever seen. “Kenny, did you repaint this milling machine housing?”

He stops work on the jack and comes over, “It was really ugly, I couldn’t stand it that way, I reshaped the housing, then I made new trim pieces, then I shot it in catalyzed enamel…”

This leads to a complete cessation of work on the jack/Alfa while he shows me his amazing portfolio. There are cast iron springs done for a French iron and steel company, a $35,000 hors d’oevres cart (“I lost money on it.”), models for films, models for collectors, prototypes for designers, sculptors, automotive reproduction trim made by sculpting in wax, then electroplating the wax to desired thickness…we wander back over to the jack. It’s the most beautiful floor jack I have ever seen.

At lunch he suggests chili and tamales. I have to reassure him all over again about the life expectancy the the car, the gentle nature of vintage racing, my overdeveloped sense of responsibility, I promise I will wave on every lap…the chili gives me indigestion.

Back at the shop it takes him fifteen minutes to finish the jack, ten to install the crossmember. He drives me around the block in the Alfa, fills the tank (21 gallons—Veloces were originally built for the Mille Miglia. Or maybe there just weren’t many gas stations in Italy in 1959.), wishes me bon voyage, and I’m off.

I’m well outside of Sante Fe when it hits me: I’m driving a 26-year old car, one I have never driven before, one that hasn’t been driven much in the last couple of years. It has a highly tuned 1300cc engine—smaller than some motorcycles, an electrical system known for caprice, a thousand pitfalls waiting, one for every mile I have to drive. I hear a hundred things going wrong in the next hundred miles. Each one turns out a false alarm.

After that I relax and the trip turns into one of those dreamy fantasies, spinning across the open high desert, passing newer cars, cruising at eighty, the Veglia tach bouncing around the “40” mark. The gauge starts at “20”, nothing less is considered.

After a while there’s a strange ache in my face. It takes me a few minutes to realize I’ve been smiling for two hundred miles. I have to refill the Veloce only once—it’s averaging just over 30 mpg. The sunset takes a long time to fade and I’m into California before I pull over to sleep for a couple of hours.

August 4, 2pm. I arrive home with six bucks left.

August 4, 5pm. Over to a friend’s shop. We put the car up on jack stands, pull the brake drums—plenty of lining, no leaks. He has his guy fabricate a new exhaust pipe that replaces the front muffler, leaves the resonator, and ends with a flattened megaphone that exits in front of the left rear wheel. It looks great and makes a terrific racket there in the shop. And it fits inside the car so that I can get it to Monterey. I get to bed at midnight.

August 5. Up late. Over to Tony’s shop, VRS. We put the car up on his rack, drill the drain plugs for safety wire, mount the seat belts and harnesses, safety wire the clasps, borrow a fire extinguisher, install catch tanks. Spend a long time looking at things–brake lines, water hoses, clamps, electrical connections. Nice guy—he buys me dinner. Everything goes smoothly and it still takes twice as long as I think it will. That last six bucks goes into the tank.

Tired. I get to bed after midnight this time. And I can’t sleep.

August 8. Up to AEM. John’s a carb expert. I’m worried because the car shouldn’t have gotten such great gas mileage—I’m afraid it will run lean at wide open throttle. He stops work and lets me run the Alfa on his chassis dyno—74 bhp at the wheels—very good he says (rated at 103 bhp/SAE gross at the flywheel). It makes four more horsepower with the megaphone and the air filter removed. It’s not lean at anything above idle. Vegher did a great job. I’m happy.

August 11. A check arrives in the mail from a story that I wrote so long ago I can’t remember what it was about. Elated. It inspires me to work on another (slightly) overdue story. That night I go over to mooch yet more shop time—Ward & Deane—they’re open nights. We get the car up on jackstands and Ward pulls the front Konis to adjust them while I change the oil.

After I wire the drain plug in place I pour in the 20/50 Castrol, change the filter cartridge (it’s the old fashioned type with a separate filter inside the housing), reach in, while Alan is under the front reinstalling the shocks, pump the gas pedal once with my hand, flick on the key, start the car and dump about four quarts of Castrol on Alan’s head. At least it’s not hot.

Remove the filter housing, reinstall it straight, squeegee the oil and scoop it up with a dustpan, wipe down the floor with solvent. Cadge more oil, check the valve clearances—all OK. It turns into another late night.

August 13, 14. Lie to an editor on the phone. Spend the rest of the day writing. I keep stopping to go over the lists and lists of lists to see what still has to be done.

August 17. Prevail on Morse again who prevails on Steve who will make the numbers for the car–192. Finish the story and deliver it. The editor snarls at me. I use the magazine’s phone to call a few friends, one of whom may just have a floor for me to sleep on. A penny saved.

August 19. Up to Doug’s to pick up the wheels and tires, they fit inside the car if I leave the stock spare out. Home. The exhaust system fits on top of them. Gene calls and says I can sleep in his room. Bring my sleeping bag. It fits too, so does the tool box. Things are going much too well and I worry about that some.

Kenny calls me late at night, wakes me, wants to see how things are going. He has made reservations to fly to LA. For a panicky moment I’m afraid he’s changing his mind. I tell him about the dyno test, the oil spill, the exhaust system, talk to the parrot. I have trouble getting back to sleep.

August 20. Pack my new driving suit, full face helmet, gloves, tee shirts that Kenny has sent me (they have Alfa 1750 engine cutaways on them, incredibly detailed), jack stands, a fuel can, tape, wire, another set of plugs, more oil. I would never have believed that the little coupe would hold this much. Make calls, go to bed at 11. Plan to leave a 6am. Can’t sleep. Get up at three, on the road at four.

August 21. It’s about 350 miles to Monterey, about six hours. The car is so full I can’t see out of anything except the windshield. I stop at a doughnut shop for two plain cake and coffee. I want someone to ask me about the car, about where I’m going, what I’m doing. It doesn’t happen. Driving toward the freeway, a cop drives beside me for a while, disappears. I think he’s following. Paranoia.

Stop again 150 miles later in Santa Barbara at the coffee shop by the big tree. Leaving Santa Barbara I see Larry Crane (now Automobile Magazine, then R&T) and his Lancia Aurelia headed north. We drive together for a few miles, then he stops to wait for his chase car. I’m alone again.

I see a few trucks pulling enclosed car trailers heading north toward the races or the concours at Pebble Beach. At the same time that I am envious of their (financial and real) security, I have this little glow of pride in having done it The Way It Used To Be Done—i.e., drive it to the races, race it, drive it home again (I hope). A truck and trailer would be nice. So would a box full of tools, some spares (an engine, a gearbox, etc.), my own hotel room, enough money to handle contingencies (like the aerial surveillance speed trap outside of King City).

The first sports car race I ever saw was at Walterboro, South Carolina in the spring of 1956—right, 1956. It was Briggs Cunningham’s D-Type Jaguars against Jim Kimberley’s Ferrari 121LM (Jag won), XK-140MC against 300SL (SL won), Porsche Spyders, Maseratis, Wacky Arnolt’s own team of Bristols, a whole collection of cars that have become objects of worship now. The memories are clear, and the very clearest of all are The-Kid-on-Christmas-Morning, Nose-Pressed-Against-the-Toy-Store-Window feeling that I had. And I can’t help it, I still feel that way driving past the entrance to Laguna Seca. No one there today except security guards. One trailer truck from a high-buck restoration facility parked by the side of the road. I wonder if they couldn’t sleep either.

I have dinner at the Chinese Village in low-rent Seaside, sit at the counter alone, think about things for a while, and finally spend the night sleeping in the car in the parking lot. The inside of the car smells like tires, the wind blows damp sea air through to mix with the tire smell—I have no trouble sleeping.

August 22. Breeze through registration. I always always hold my breath—probably a hangover from the days when I raced an old Speedster and left everything to chance and until two minutes after the last minute.

Next to my assigned paddock space is a nice guy driving an Alfa SZ—his car is perfect. The SZ has the same chassis as the Guilietta Spider (shorter than Kenny’s Sprint) topped with a curvy Zagato aluminum body, lighter and better aerodynamically than the stock Sprint, and pushed around by an engine that’s in a higher state of tune than the regular Veloce. I want one.

We’re talking about the wonderfulness of it all while I unload the car. He sees my tires: “Michelins…” he says with that note in his voice,”…you can’t race on those.” He seems genuinely concerned. He has real Dunlop racing tires on the SZ (about $220 a copy). Their shallow tread isn’t even dirty.

“They’re what I have.” It sounds lame as soon as I say it. For a while I’m afraid that there has been a ban on 70-series tires (80-series would have been low profile when the Giulietta was new), but there are 70-series tires all over. Later I see my neighbor casting doubt-laden glances and pointing them out to some of the others in our class. Psyching me? It works (temporarily).

Tech inspection–another breath-holding exercise for me—is a snap. They check the wheel bearings without jacking the car up, ask me if the drain plug is wired, but seem concerned that the belt of my safety harness (“like Prost uses”) is too narrow. They remind me about the numbers (Where’s Steve?), and tell me to tape the lights. Finally, it’s OK, and no one says anything about the tires.

I have involved so many people in this project that my paddock space turns into a mob scene—people taking pictures, wanting me to pose, wanting me to get out of the picture, wanting to help, wanting to talk. All of this attention is confusing to my neighbors, both of whom have cars far more exotic than Kenny’s.

Kenny wanders off to see if he can find some red tape for the lights—he hates the way silver looks. Steve shows up and puts the numbers on for me, someone runs off and makes color Xeroxes of the paddock parking pass (Very, Very definitely frowned upon). The recipients of the fake parking passes then spend hours grousing about how crowded it all is and certainly Not The Way It Used To Be. I have to find a place to stay.

August 23. Kenny got the extra bed in Gene’s room, I sleep on the floor in Gooley’s room but his lady friend will be up tomorrow. I elect not to eat breakfast and drive the Alfa out to the track being careful not to make too much noise. Just before I get there, a Ferrari 250 SWB passes me sounding like the start at Le Mans.

My practice is on mid-morning and for the first time I get into the car wearing the driving suit and my full coverage helmet. The Helmet hits the roof, the belts have to be readjusted, when did I last check the gas, what are the tire pressures, did I finally get a lock washer on the exhaust pipe hanger…and out onto the track about a hundred yards behind a TR-3. This is just practice this is just practice this is just practice…I catch the TR-3 (who is cruising) before turn three. We’re under a yellow and I can’t pass him and I keep yelling at him to go faster, to close up on the red car that is now disappearing around turn four about three hundred yards away.

Testing has shown that the resting heart rate of a driver in superb condition may be as low as 55/57, but that as soon as he gets into the car, just gets in, it goes up to about 135. Under racing conditions it’s over 200. Mine was 135 before I got into

the car. I didn’t hear the last six things that anybody said to me. I have enough adrenaline going to pick the Alfa up an run with it–but I still can’t pass under a yellow because we’ve been warned about all of this–obeying ALL flags, making NO transgressions. So I’m sitting here screaming at the TR-3 in front of me and I’m still on the first lap of practice.

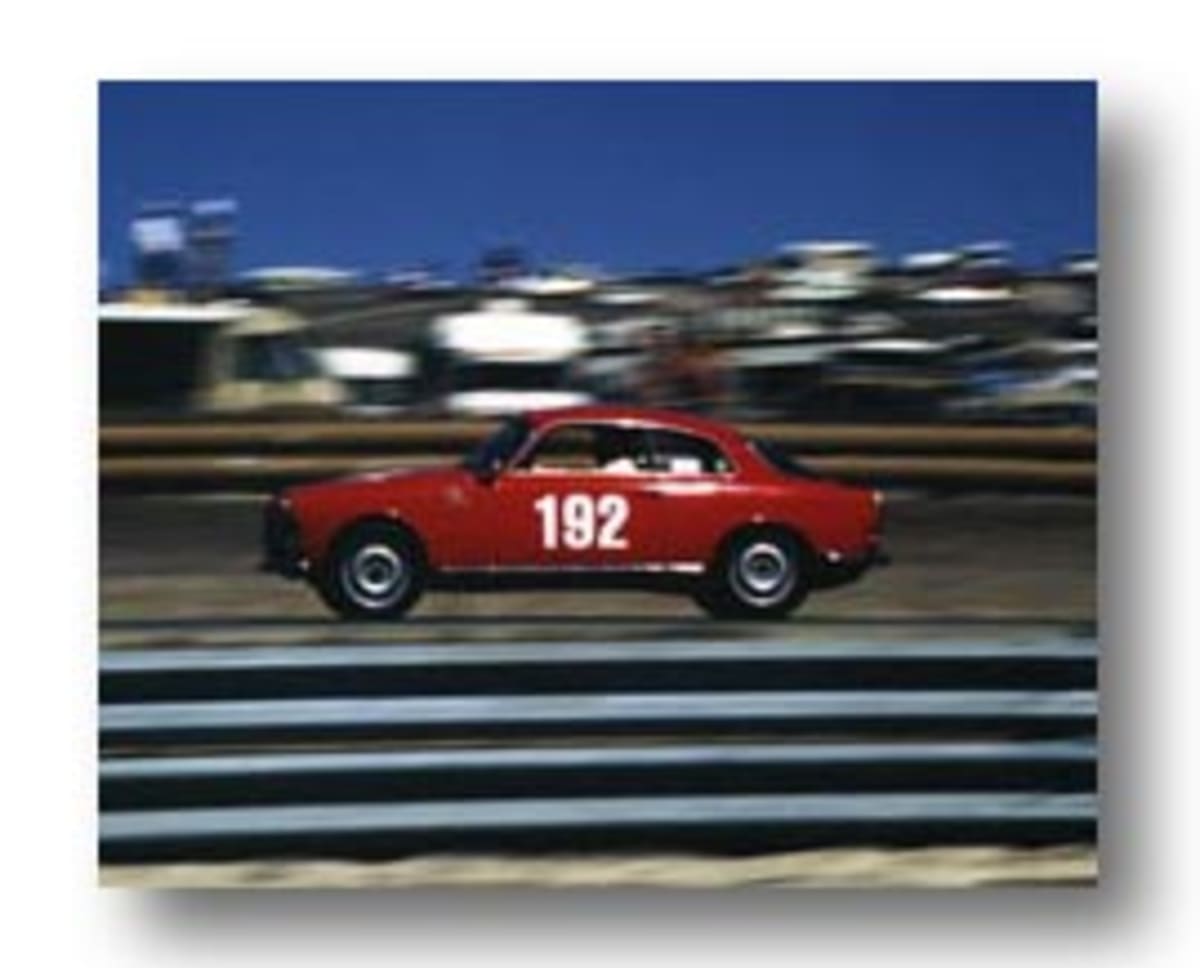

We run about three laps under the yellow, by which time I have stopped screaming and my heart rate drops to normal–around 180. Actually nothing untoward happens during practice–the green comes out, the TR-3 continues to tour and I’m by him in a comparative flash, remembering that I’m in a car that weighs well over a ton and has an engine smaller than the Big Gulp at your favorite stop-and-rob.

By the end of the session I’ve passed a few cars, a few more have pulled off, it’s kind of lonely out there. I’m still trying to figure out whether I should run it over 7500 in fourth momentarily between turns three and four, or whether it’s faster and easier on everything concerned (it’s Kenny’s ride back to Santa Fe) if I take the time to go up to fifth then back down to fourth and whether I can carry enough speed to go through turn four (a near-90% uphill left that’s faster than most people think–a very important turn for a small displacement car that doesn’t have a surplus of torque to help it up the long steep hill that follows), in fourth.

I’ve spent my time out there trying to relearn the track. Practice is officially a half hour but it’s actually a paradox of time. At my accelerated adrenaline level, everything happens in very slow motion: vision is acute, there is more than enough time to examine mistakes and swear at myself for making them, enough time talk to my hands, my feet, my knees, one at a time as if they were untrained children stumbling through some clumsy dance.

The timekeeper in my head is badly confused by all of this and if I hadn’t seen thirty minutes on the schedule I would have put time on the track closer to ten. Off the track after the checkered flag lap and back to the paddock where I’m given some lousy time as my best lap. It’s three seconds faster than my neighbor’s SZ. I still wonder what the problem with my tires is?

I’m suddenly very, very tired. It has less to do with conditioning than with the adrenaline tap being turned off. What is it Adele Davis suggests for exhausted adrenals? Morse comes by and asks me when I’m going to do it with the engine on. Kenny sees it the other way–am I not being too hard on the car, should I not save something for the race? Gene wants to get lunch. Mark wants to drive the car around the paddock. Ray shows up and wants to check things over. I tell him to check the oil, then have to show him how to open the hood. Gooley says he got some great shots.

Finally, enough energy to walk around and look at things, pretend to myself to be writing a story about Monterey, eat an ice cream cone, eat a hot dog. See Browne who wants to know if I’m going to this hospitality tent, that reception, The Big Dinner.

There are cars everywhere, about half of them red. A few semis each with an array of fantastic machinery out front, uniformed crews, awnings, pavilions, caterers, drivers in tailored Nomex lounging with attentive ladies (a few women drive but it’s still a male-dominated sport), what am I, with my sleeping bag, depending on the kindness of strangers, doing here?

I’m surveying my competition, that’s what, and most of it, though better off financially than I am certainly hasn’t arrived via 18-wheeler. There are twenty-eight cars entered for this race: a bunch of Alfas—four of the lightweight Sprint Zagatos, including two SZ-2s (better aero), four Sprint Speciales (heavier but more aerodynamic than the SZs), half-dozen Spider Veloces including one called a Sebring Monoposto, four Sprint Veloces counting Kenny’s and a couple of the early 750-series Veloces which are lighter than the late 101 cars (ours). There are two Alfas that are supposed to be 1600s, the rest are 1290cc like ours. There are a pair of TR-3s (one with drum brakes)—the Triumphs have big four cylinder tractor engines that displace somewhere between a legal 1991cc and about 2.2 liters. A pair of MGAs, one a rare twin cam (with four wheel disc brakes stock) and nice, easy handling—no nose dive, no body lean, no bad habits at all. Three Porsche 356As–one Convertible D and a pair of Speedsters, and a couple of Fiat-Abarth 750s.

Some of the cars are old race cars with international histories–the Sebring Spider, for instance, suitably enhanced for modern vintage racing. Some are just old SCCA race cars, unearthed from garages and dusted off (we are told), some are fanatically restored—too perfect to believe (my neighbor’s SZ), some are just street axes with pretentions (us).

That night Gene, Kenny, and I go to a party held by another friend who annually had crashed his Bobsy and was now looking forward to having a 750 OSCA streamliner with a birdcage frame restored so that he might race that (without crashing, he hopes). Eat a little, try not to drink anything, try not to worry about the Alfa parked back at Gene’s hotel a few blocks away. Try not to think too much about the race tomorrow. Try to get to bed early. Fail.

What did I tell Kenny? Vintage isn’t real racing, just an exercising of wonderful old mechanical horses. And we all know what certainly follows in the wake of horses. This night Kenny takes the floor (coddling the driver?) and I get the spare bed. I can’t sleep anyway.

August 24, Race Day, Saturday. This whole project has occupied a huge chunk of my waking hours for the past five months, and, I suspect if I ever remembered my dreams, far too many of my sleeping hours.

Gene and Kenny drag me off to one of the slightly too cute, much too crowded breakfast places in Carmel near the hotel. There’s fresh orange juice with pulp (it makes me think of trash floating in the oil, waiting to wipe out a bearing), crisp bacon brings fast-fading brake linings to mind (prophetic). I find no automotive analogy for scrambled eggs. Off to the races.

Somehow I got the car out to the track in plenty of time. Somehow I checked the oil, re-repaired the exhaust megaphone (it was splitting from resonance), checked the oil again, the tire pressures, looked in vain for something to change, something to fix, some assurance that it was all going to be OK.

No torture—I didn’t win. In fact, Steve Earle doesn’t award trophies, doesn’t honor winners–it’s participation that matters. We participated. Maybe even a little better than that. I took my place on the pre-grid somewhere near the middle of the group—about twenty-three cars actually started. There was a Alfa in front of me, a Porsche Speedster behind me. Kenny was petrified and, after posing for Gooley, wandered off to sit down. Morse came by and said, “It’s the biggest used car lot I’ve ever seen.” Gene was wandering up and down taking pictures. Alan came by and said, there are only two 1300 Alfas running—yours and Leake’s (the Sebring Spider).” Leake had the pole.

Hours (it seemed) later it was time: the pit steward blows a whistle, gives the signal to start the cars—I’m struggling into my helmet, my gloves, looking frantically around for someone to help me with the belts. My de facto pit crew has fled to favorite corners. Someone—I have no idea who—helps me strap myself in at the last second and, pulling down as hard as I can on the harness tabs, I pull out on to the track behind another red Alfa.

The races are supposed to be twelve laps each if you don’t get lapped. The first lap, however is a pace lap under the yellow, so the races are eleven laps, about 1:35/1:40 per lap—call it 17 minutes. And although I certainly wasn’t thinking about it then, I am now: what an amazing expenditure of effort, money, and time for 17 minutes—kind of like sex (gone wrong), but better, for me at least, than drag racing.

I don’t really jump the green flag but I do hop it a little and pass the two cars that started in the row in front of me. As I approach turn 2, I see Leake in the Sebring Spider exiting turn 3—he’s all by himself. Turns 2 and 3 are (actually were—a whole artificial section has been inserted between 2 and 3) right in the middle of the fastest part of the track. Laguna Seca is (was) a natural track—it follows the contours of the natural amphitheatre that surrounds it and has turns probably never seen in “designed,” artificial tracks.

Turn 1 in anything short of a hyperactive `60s USRRC car (like the one I race now) doesn’t exist. Turns 2 and 3 are very fast lefts taken as close to flat as the car and driver allow. A mistake at 2 translates to disaster at 3 even though they’re not too close.

Turn 4 was mentioned before—about 90o uphill left, faster than it looks, very important for a small-bore like the Alfa. Turns 5,6,7—the Corkscrew—are the most photographed and least important turns on the track. They are tight downhill turns made for telephoto compression. Eight is a fast, wide, downhill left that scares me, and leads to 9, yet another left, this one slow (maybe 35 mph), acute and important because it leads into the fastest part of the track.

As I approach 4 on the second race lap, there are flagmen on both sides waving blue flags, indicating that someone is trying to pass me. I have taken the Driver’s Meeting Oath to obey all flags scrupulously least I not be invited back. Dutifully I move over and let a guy in a Speedster (I find out later that it’s an SCCA car that he has owned forever, an active racer until about ’75) by. Certainly this not the first mistake that I have made on this day, but just as certainly it proves to be the worst.

From turn 4 lap three until the very end of the race, this guy is in the way. He can out-accelerate me from 9 but I seem to be willing to go a little faster most other places. Remember that a Speedster comes in at 1600 lbs. and the Alfa about 500lbs higher, the Speedster is (or was) a 1600, the Alfa a 1300, the Speedster a race-prepared car and you already know about the Alfa. Given a little more time I could conjure up even more valid excuses but the truth is that the blue flags are advisory only—when they were waved at him, he waved back and didn’t move over. I was never more than a couple of car lengths back but, with fast fading brakes I couldn’t quite bluff him into giving way entering a corner and I never had quite enough power to pass on the straight parts. Lord knows I tried.

A few laps before the end I noticed a little knot of people standing at 9 cheering me—I finally realized that they were track marshalls and felt really good about that. In the last couple of laps I’d start to come inside on bizarre lines and the Speedster would move over to block. I began wondering what the price of the left door on the Speedster was, but then Kenny had to drive home, and Earle frowns ever more sternly on car-to-car contact, and then it was over and for one cool-off lap, I felt pretty good.

Leake in the Sebring Spider won, came within maybe ten seconds of lapping me. A couple of Porsches followed, trailed by the MGA Twin Cam, a lightweight Veloce Spider, then came the Speedster, then me. All the SSs, SZs, were somewhere behind me. I never found out why I couldn’t run on the Michelins.

Everyone was happy, hands were shaken all arounds, backs, mostly mine, slapped, Kenny stopped worrying about the car and went off on a fantasy about future races—no one listened except me, and I didn’t believe him.

Post-partum racing—what a friend calls the feeling that you get after the last race on the year. I had it then, I have it now despite having run dozens of times since then in everything from an Archer Brothers Spectrum on ice (we won), to a Thomas Cheetah that feels like its on ice all of the time (I haven’t won—yet). It’s a disease. I have no advice, no cure, no finish for this except to say that–take this as a warning—I no longer see blue flags.

Top image: Palette knife illustration of the official poster by Jack Juratovic of the 12th Annual Historic Automobile Races, Monterey, August 23-25, 1985, held at Laguna Seca Raceway.

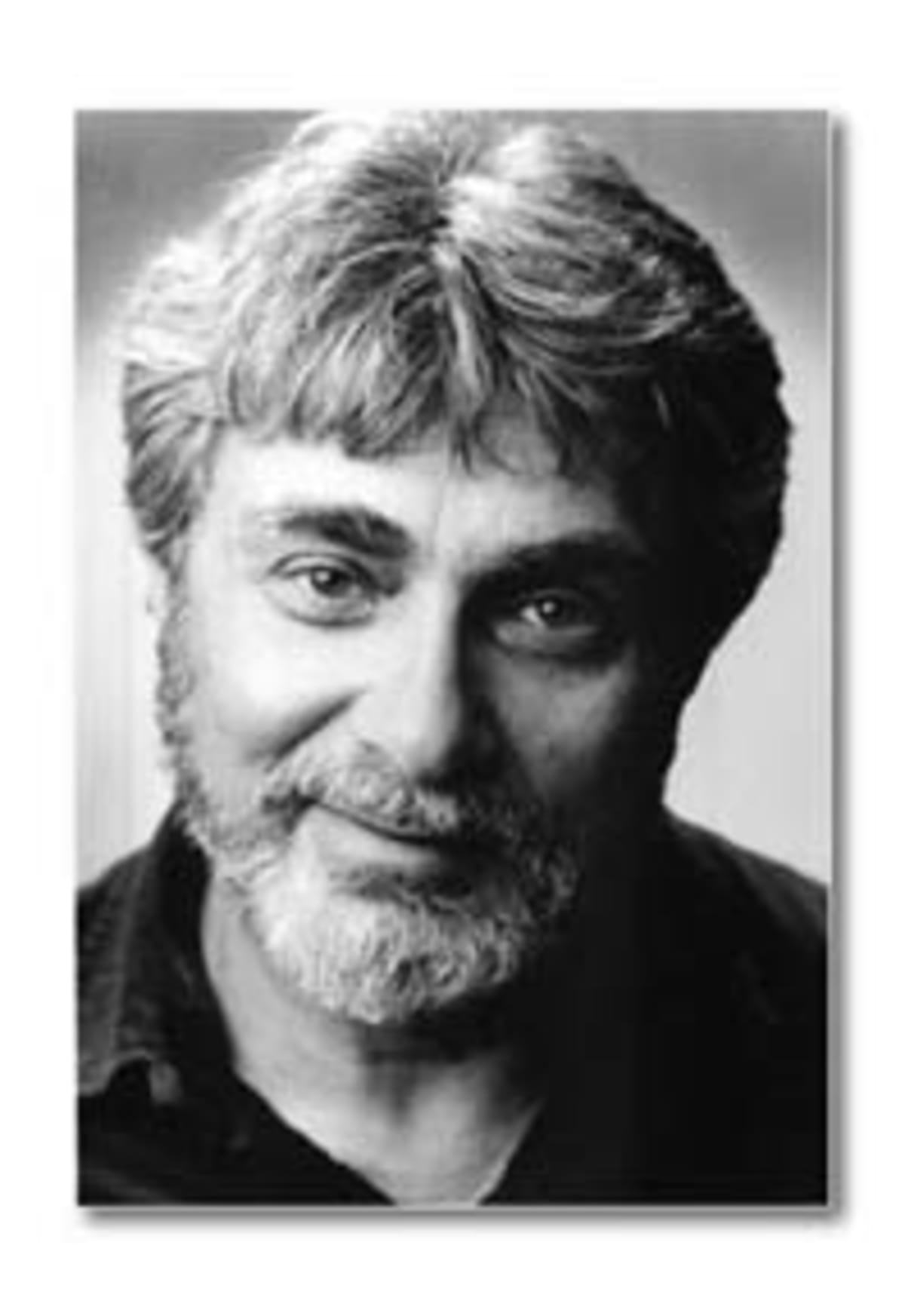

The late Len Frank was the legendary co-host of “The Car Show”—the first and longest-running automotive broadcast program on the airwaves. Len was also a highly regarded journalist, having served in editorial roles with Motor Trend, Sports Car Graphic, Popular Mechanics, and a number of other publications. LA Car is proud to once again host “Look Down the Road – The Writings of Len Frank” within its pages. Special thanks to another long-time automotive journalist, Matt Stone, who has been serving as the curator of Len Frank’s archives since his passing in 1996. Now, you’ll be able to view them all in one location under the simple search term “Len Frank”, or just click this link: Look Down The Road. – Roy Nakano