An Unscheduled Trip

Published on Sun, Jan 1, 1989

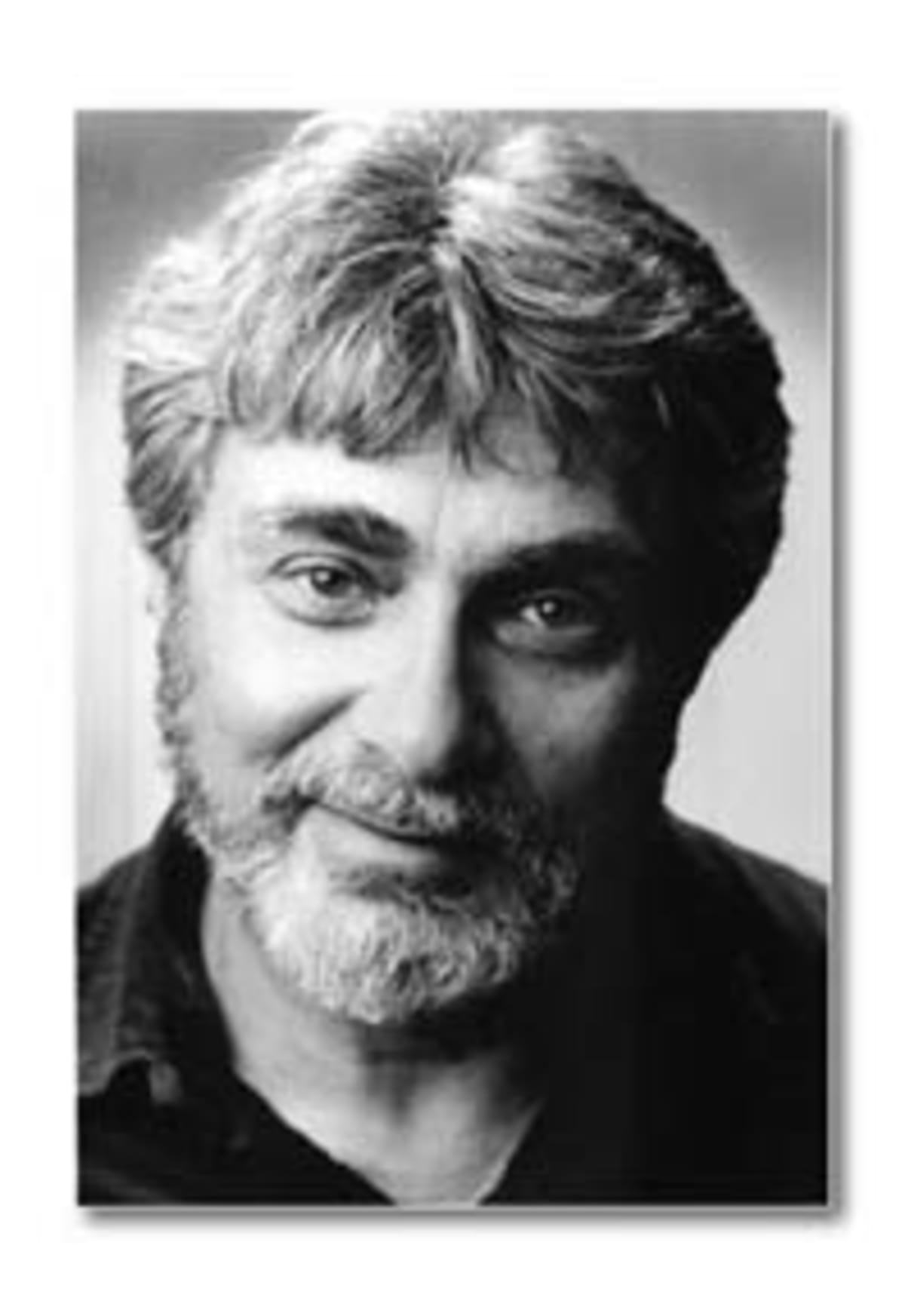

By: Len Frank

Porsche Cars of North America’s Hal Williams calls Len Frank and says, “We’d like you to take a long trip in one of our cars.”

No one drives to work on a skid pad. There are a few cars that are best shown off there, but after all it’s day-to-day experience that determines the balance of the love-hate that is obsessive car ownership. Those experiences are very difficult things to put into the neat little spec boxes that magazine art directors so love. The inherent problem, the weakness, the fallacy of magazine road test procedure is that there is too much “test” and not enough “road.” The solution to the problem is obvious but usually impractical to implement. This time the obvious became practical and there was no dragstrip, no skid pad, no spec box to be filled in. Just the day-to-day experience. Love and hate follow.

DAY-TO-DAY EXPERIENCE

Day One:

Porsche Cars of North America, in the person of Hal Williams, is on the phone. “We’d like you to take a long trip in one of our cars.”

“Where?”

I know, I know. It’s the automotive equivalent of being asked to spend a month in a tropical paradise with Kim Bassinger and asking which tropical paradise, and will there be room service. Sometimes room service can be very important.

“Anywhere you like as long as it’s a long trip.”

“Can I get some color other than red?”

Don’t bother applying for my job. My traces are firmly in place, but my driver’s license dangles by the thinnest of threads. It is not fighting bulls who are enraged by the sight of red, it’s sundry law enforcement officers. Maybe it’s why the police were called bulls long before they were called pigs?

ALTERNATIVES

The modest vacation that I had planned for the holidays entailed taking some anonymous car loaded with all of my half-read and unread books to Guaymas on the west coast of Mexico. Nobody goes to Guaymas. Mostly the sun shines. It’s a shrimping port. There is cerveza. Perfect.

I have also been invited to Denver by a friend. We will stay with her parents. She has already made plane reservations “just in case.” It’s not that I hate flying: I hate commercial flights, airports; I hate standing in lines, fear cancellations, despise myself for eating the airline food, worry about lost baggage, terrorism at the rental car counter—the whole plague of modern, convenient, time-saving travel. There is no adventure here, no pleasure; only delays, discomfort, anxiety, empty promises, boredom, and this the heaviest travel season.

The phrase “grand touring,” drifts into mind. We are surrounded, besieged, by variations on the GT car. We have in addition to GTs,GTAs, GTBs, GTSs, GTIs, GTis, GTXs, and GT etceteras, but seldom are any used for anything like grand touring. Grand touring was once common enough but now it has become largely a fiction of advertising copy writers trying to get us to buy more cars (or beer, cigarettes, sunglasses, etc.).

Grand Touring—my definition—allows me to experience the pleasure that the designers and engineers have built into the machine, rather than what some four-color glossy brochure tells me I’m supposed to find there. It allows me to compress time/space, to see an endless cinematic triumph in living color through the windshield. It allows me the illusion that I am setting my own schedule. It might be two-and-a-half days from the Daytona 24-Hour to LA, or it might be three-and-a-half to travel the 375 miles from my home to The Monterey Historics. It means no franchise joints, local radio when I get tired of cassettes, no Interstates. Above all, no Interstates.

AN INTERVAL PASSES

I accept my friend’s invitation to accompany her to Denver, but only if we can drive.

“Drive?” I can tell the word has a foreign ring to it. “Drive” is how one gets to work every morning. “Drive” is what one tries to avoid doing when going to the airport to go somewhere. “Drive?” she says, “How long would that take?” “I made it from ElAy to Pikes Peak in about eighteen hours once—two of us driving—it’s maybe a thousand miles…but I had something more interesting in mind.”

What I had in mind was most probably interesting only to me and probably involved not going to Denver at all. I can zig-zag happily up and down all of the back streets and secondary roads of America, not really going anywhere at all. I mean, where is there really to go, anyway?

“How would we get there? Would we stop in Santa Fe? I have friends there. If we time it right there will be dances at the pueblos…maybe we can go skiing in Denver…”

Guaymas will be there next year.

The Car is ready on December 20, a Baltic Blue Metallic 928S-4, automatic, interior in linen-colored supple leather with leatherette piping, electric lumbar supports, limited slip diff., Blaupunkt Reno AM-FM stereo cassette sound system. A nice piece, as they say in the trade.

I mutter something about winter weather and fat V-rated tires and incompatibility but I think it all goes unheard in the talk about packing lists. At the last minute I forget my sweaters and parka.

NUMBERS

Let me get the easy part out of the way first. When I picked the up the 9-2-8, the cumulative fuel mileage readout was at 14.6 mpg for the 2447 miles on the odo. When I returned it, it read 19.0 mpg for 5657 miles. In other words, in 3210 miles I averaged enough over 20 mpg to bring the overall average up almost 4.5 mpg. Dumb numbers. And it certainly wasn’t an economy run.

For what it’s worth, this 928S-4 with automatic gets 24+mpg at 80 mph, 20+ at 100 mph, 14.4 (about) at 120 mph.

By coincidence, the fastest I have ever driven in an automobile and the fastest I have ever driven on open public roads both involved Porsches. The first was in a 935 at Riverside when it still had its long back straightaway. The owner of the car told me that I was driving his child’s inheritance, and please be careful, and don’t exceed 6700 in top gear. When I got out of the car he told me that 6700 with the installed gearing was something over 170 mph, and that the front Goodyears were old and hard, and that if I had tried cornering hard it would have understeered right off the track.

Swell.Rotten old tires or no, it was marvelous to drive and had the best brakes that I have ever used. But the 935 is really just another perversion of the term “GT,” at least until somebody figures a good way to get the roll cage to double as an antenna.

The 928 would do 162 on the analog speedo (the digital readout agrees). I was a little disappointed because the owner’s manual claims 168. Of course it was an automatic and I was at well over 6000 feet.The first time I put the absence of a radar detector out of my mind and my foot down, we were headed north in southern Colorado somewhere between Monte Vista and Salida. And anyone tall enough to reach the gas pedal and see over the cowl at the same time could have done it.

Even at that altitude, the 928 gets up to about 140 in one big rush. It shifts itself into fourth (the automatic has Mercedes internals) at about 120 and pulls, strongly about the way some lesser sporting vehicle might pull from 60 toward 80. Very nice piece.

ABOUT THE CAR

The 928 has been around long enough to almost start being called a “classic.” It was one of the first whole cars to have been designed under Anton Lapine who just left Porsche, and one of the last to have been engineered under Prof. Fuhrmann. When the 928 was conceptualized (I think late `sixties, the official word is 1973) we lived in an expanding universe. There was the spectre of emission controls and safety regulation but in general things looked they might only continue to get better. The OPEC oil embargo changed all of that and final approval for production of a car that now carries an $850 Gas Guzzler Tax was a further affirmation of that expanding universe. The actual production 928 was shown to the public in March, 1977 at the Geneva Salon.

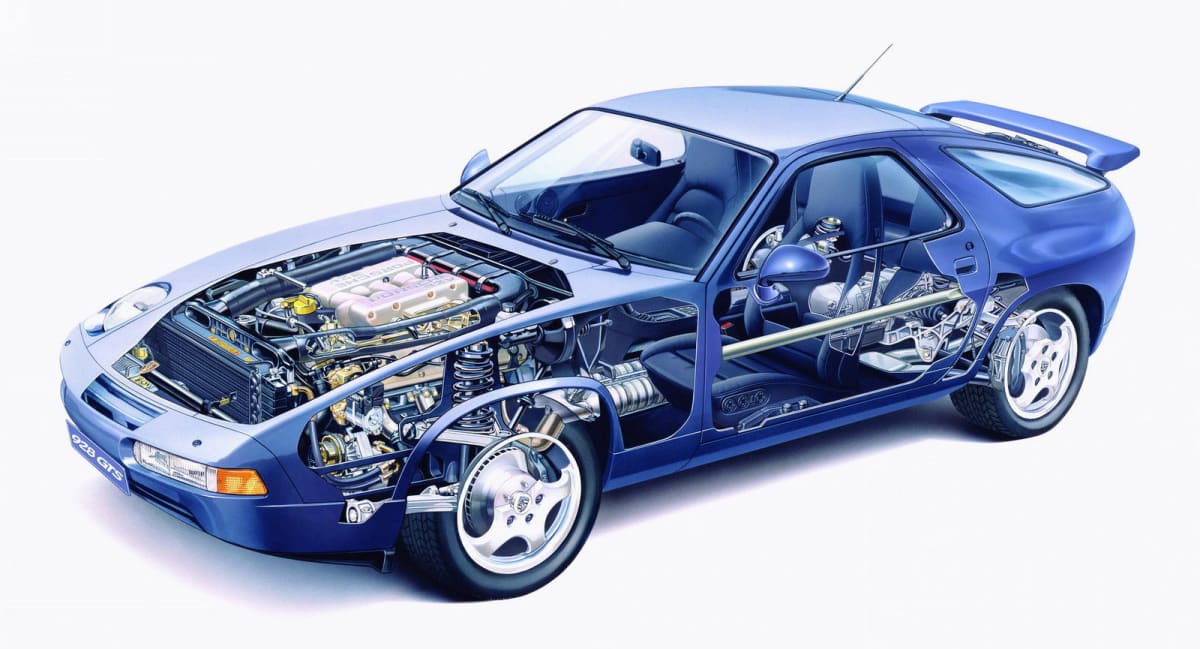

The 1989 928S 4 is on display now and it’s really very much the same car as it was a dozen years ago and exactly the same kind of car as it started out to be (unlike the 911)—that is, the best, most luxurious, highest performance GT car that Porsche—or anyone else—could build. Briefly, it’s a unibody car with a standard small, electric sunroof, a hatch, solenoid operated, and two wide, thick, doors. Those doors are hard to open in tight side-by-side parking, the huge rubber (Dunlops, 225/50VR16front, 245/45VR16 rear) limits wheel lock making the 928 a little hard to parallel park. The usable glass area is small, and while the occupants don’t see out very well, it certainly keeps the hoi polloi from seeing in. Altogether a rather imperious, slightly antisocial car. It is the philosophical antithesis of old Ferdinand Porsche’s most famous creation, the original VW.

The suspension has only had detail modification over the years—anti-roll bar diameters, spring rates, shock valving, wheel diameter and width. Tires, too, have come a long way since 1977. It’s a tribute to the original 928 design that very little had to be done to the parallel A-arm front suspension or the Weissach rear axle (which seeks to minimize roll steer and toe change—very important when a 245-section tire transmitting 300 hp wants to start steering as well) to keep the 928 among the best, especially considering the excellent ride.

The body hasn’t really changed since it’s introduction.A rear spoiler was added, then changed to a wing type. Judging from the exceptional stability at considerable speed, it works. The 928 wasn’t the last word in low drag designs when it was designed and any little improvement made in changing spoiler shape was certainly cancelled by the increased frontal area of increasingly larger tires. The engine just rams it through. Brute force.

Does this sound critical? Was Zero Mostel (in “The Producers”) the first to use the line, “If you’ve got it, flaunt it.”? Someone at Porsche applied it to this imperial automobile. One can just about count the number of cars sold in the US that will break 160 on the four fingers of Mickey Mouse’s white gloved hand.

But the 928 is the only one that comes with luxury items like a real dealership network. Porsche currently is running an ad that asks you to think of the 928 as a Mercedes with Tabasco, the implication being that ownership of a 928 incurs little risk and big excitement. It has a real warranty, parts are not lost in the hold of some rusting Italian tramp steamer, you can wander through the classifieds in any big city newspaper and find one with 100,000 miles available for inspection. That’s the little risk part.

The big excitement comes from under the long hood. When the 928 was introduced, the SOHC V8 had 219 SAE (net) hp from 4.5 liters. Now, with DOHC four valve heads that fill the available space and 5.0 liters the S 4 has 316. All of the 928s have used the Reynolds 390 aluminum/silicon process with the pistons running directly in the unlined cylinders—less weight, better cooling, better wear characteristics, simpler construction. The irony here is that the first production engine to use this system was the unlamented Chevrolet Vega, and now that Chevrolet has embarked on the very limited production of their similar (to the S 4) LT-5 engine, they seem to be afraid of the 390 process despite years of success by Porsche (and Mercedes).

I have already mentioned the gas mileage and top speed, but just as remarkable is the smoothness, the silence, the throttle response. Remember that I picked the car up at sea level and worked my way up to well over 11,000 ft. It ran as cleanly storming a pass over two miles up as it did crawling through LA traffic. You can thank the dual runner intake manifold that broadens the torque range and the Bosch engine management system combined with the LH-Jetronic injection. It’s hard to find premium fuel at high altitudes, but Porsche uses a pair of detonation sensors to retard timing for just such a situation. All this praise is not some magazine cop-out—there are things wrong with the 9-2-8, some rather stupid and thoughtless items, and eventually, I get around to them.

THE TRIP

But I left off at low altitude, sans parka and sweaters, trying to leave LA at peak traffic hour on the 20th of December. Traffic in LA replaces weather in most of the US as a topic of conversation, and like the weather, damned little is ever done about it.

Denver is north, east, and uphill, from LA, and so to get there, one normally goes north, east, and up. There are a bunch of Interstates that can be employed but you remember what I think of Interstates. However to get out of LA, in the dark, in the rain, with the holiday frenzy well and truly settled in, I compromise. After forty minutes and fifteen miles of going south and east, dinner seemed like a wiser course.

There is something almost subversive, and certainly coercive about the I-states. They too often don’t supplement existing roads—they replace them all together. The interstate goes in and soon, like laser-seared varicose veins, the other roads wither and die, choked with traffic controls that weren’t there when they were main traffic arteries. Sometimes they remain, surrounded by the fossilized remains of another time—tourist cabins, independent gas stations, junk cars, queer cafes, Bates Motel.

There are other problems with the I-states. They hide the country. They cut through mountains, fill in valleys. Every curve is minimal, every grade is gradual.There is one relief from monotony: cops. I would rather be bored. Where is the World of the Future? Why don’t we have bullet buses running on these things?

TO DENVER

It’s raining. I have eaten too much indifferent fried chicken and the cholesterol demons are busy snapping my arteries shut. My companion and I are having our first squabble. I’m tired. The car is magnificent. LA roads get greasy in the rain, but the big German Dunlops never give me a bad moment. We navigate slowly to the freeway to continue east. Once on, squabble over, we clear the LA basin in a rush.

THE PLAN

The plan is to go north on I-15 to I-40, get off of I-40 asap onto what remains of old Route 66. I-40 takes you past Bagdad (as in the Adlon film, Bagdad Cafe) and Mrs. Orcutt’s Driveway, used by various car magazines for top speed runs in lesser cars than the 9-2-8. I am able to resist Bagdad at night but The Driveway needs checking out. A couple of easy passes at 145+ on the little dead-end road. My friend asks “are we really going that fast?”Discretion overwhelms me and It’s back onto I-40 to Ludlow where I pick up 66.

IRONY

Route 66 is the Mother Road. It was the road on which The Okies (and I) came west. It was to The Grapes of Wrath as the Mississippi was to Huckleberry Finn. It was the chief funnel through which California was filled. I navigated using the Bobby Troupe lyric.I still do. Buzz and Todd, heroes of the old Route 66 series were seldom (if ever) on Route 66. The road builders, the bureaucrats, the contractors, the dippers into the public porkbarrel, the government planners, couldn’t wait to get rid of the old road, history be damned. But they haven’t quite done it yet.

So we are headed toward Kingman, Arizona, on a two-lane road, that rolls and dips and tells me a little of what the desert must have been like. And we’re doing it at about a buck-and-a-quarter while traffic, under the watchful eye of the CHP oozes along at at sleep-generating 65 clogging all eight lanes of I-40. Safety Nazis at work.

ADVENTURES

When I was a kid living in the east, one of the great treats was to eat in Howard Johnsons (always the same menu—fried clams that were like batter-coated rubber bands, followed by some kind of green ice cream) that then existed, so far as I knew, only on the Pennsylvania Turnpike. Being in one meant that particular menu and that we were going somewhere. You expected gourmet tastes from a six-year old?

By the time HoJos got to the west coast—I had preceded them by a decade at least—I was finished with the standardizations of franchised mediocrity. I try never to eat in places with plastic signs or national advertising, never to stay in places that have 800 numbers that are credit card convenient. I have been poisoned a time or two, and have met some interesting desk clerks, but I don’t recall ever having been bored. Non-standard America, the USA out of plumb, is one of the most interesting places on earth, and one of my great sorrows is the limited time available for roadside attractions—like the fence with the sign in Seligman, Az., or the Coke machine in the garage that seems to be the center of entertainment in Peach Springs.

9-2-8

We are averaging well over seventy, driving 80/90 getting a little over 20 mpg. Gas mileage is the most foolish of reasons to buy an eighty-grand automobile. Some of the less foolish reasons: the furniture; the ambiance; the presentation; the performance (of course). By furniture,I mean the certain hand with which Lapine & Company finished the interior, shaped the seats, molded the steering wheel, the dash top, the window surrounds. It’s not ergonomics—there is an impression of solidity that turns out to be real. Everything seems to be finished—no raw edges on the back side of some chunk of injection-molded plastic pretending to be something else. It may not be quite as well finished as a 1957 VW, but what is? And it is this combination of finish, positive quality, muted but audible engine sounds, low wind noise, and an impression of coddling, almost swaddling the occupants, a feeling of can-do that creates the ambiance. No one who ever was satisfied with a Chrysler K-Car will know what I’m talking about.

Every gas station attendant, every passerby (outside of LA), even the one cop who stopped me (Colorado Highway Patrol, affable officer wearing a fur cap with earflaps: he was going the other direction sometime after I had finished the 160+ run, made a U-turn, I was going 70-in-a-55 with traffic around. After the license formality, his first words were, “I’m not going to give you a citation Mr. Frank, but how fast will this go?” I told him the book said 168, but that I certainly had never gone that fast in it. Then he offered to trade me his Dodge Diplomat patrol car for the 928. Smiles all around. That’s presentation. It’s only performance that can be quantified. Just numbers.

Denver was pleasant. Parked in a driveway in an upper-middle class neighborhood, it brought neighbors out on a zero degree holiday to look and admire. The back streets of the city were covered with polished snow and ice and the 928, advanced suspension, ABS, Weissach axle, limited slip and all, was helpless. If one owned a 9-2-8 and lived in Germany (or Denver, Philadelphia, Chicago) it would certainly mean a second set of winter wheels with snow treads, traction cables, studs; it would mean great restraint with the right foot, or preferably the anonymous car (with front drive) that I was going to take to Guaymas in the first place.

DAMNABLE OVERSIGHTS FROM PORSCHE

It isn’t all Porsche’s fault, of course. We have some peculiar and inconsistent auto lighting laws in this country, but generally when a factory fits a car with driving or fog lights they only go on with the low beams, and so it is with Porsche. Although the Bosch quartz-halogen main beams of the Porsche are very good, in the Great Wide Open of mid-America, only the true sunlight of God is good enough and it seldom shines at midnight.

The road light switch on the 928 is located two switches below the headlight switch. The headlight switch itself is a twist knob with the dimmer on a column stalk. The switch below it is similar in shape but, following the rules for good ergonomics, it’s a pushbutton. The switch below that is identical in shape, feel, and method of operation. The scenario then: blasting across the prairie on high beam, approaching traffic, dim the lights, the driving lights, left on, come on with the low beams. Lights are still bothering oncoming traffic so, at 176 ft./sec., not a good time to be taking eyes off the road or fumbling with controls, reach out and push what we thought was the road light switch only to hit the one above it. This works a really handy Porsche exclusive—an extra windshield washer that uses some super stuff to clean dead buzzards off the screen. It turns on the wipers as well and surprises (and blinds) the driver.

The other unforgivable cockpit fault is an “improvement” best left to cars that try to make up for what they lack in driving ability by oversupplying “amusements”. The new 928 has a trip computer, a device that I have always felt of dubious value but Porsche’s is especially devious. BMW makes a big deal of theirs, Audi and VW relegate theirs to one button and a usable rotating menu—a good model of a questionable benefit, Cadillac, various Japanese cars, Buick (with the ultimate, a CRT), all have them.

Porsche makes theirs near impossible to operate predictably, which is fine—I simply chose not to operate it allowing it instead to tell me what the temperature was outside for a couple of days. But some genius has chosen to combine it with a fault warning system, and there you are, somewhere well to the left of double the national speed, when the thing goes into its warning mode—switching from soft amber to bright red LEDs with a flashing background–to tell you that, indeed, the gas is getting low—not very low yet, but that in the next hundred or so miles developed was also in this reporting system—it kept telling me that the coolant level was low an inopportune times. The coolant level,I determined, was fine, it was some haunted sensor at fault.

LEAVING DENVER

Leaving Denver I added two quarts of oil. Maybe it had something to do with flogging the car uphill. More likely, no one had checked the oil at any time since putting the car in service (I hadn’t before starting the trip).

Weather was not wonderful, I was not wonderful (my friend and I averaged a tiff a day, one real fight every two days for the entire journey), the 928 was at its least comfortable when ice was suspected but not seen. Climbing over passes two miles up that great engine never showed signs of altitude sickness or any of the other maladies as a result of cold and indifferent fuels—I never detected detonation at any altitude and high octane unleaded is not available everywhere.

Through Fairplay and Gunnison and Montrose to Ouray (we had come to Denver through Needles, Kingman, Seligman, Flagstaff, Albuquerque, SantaFe, past Manassa where Jack Dempsey was born, Poncha Springs, like that.) where we spent the night in a pink bed-and-breakfast because the signs all said the pass was closed—it wasn’t. Then through Silverton, Durango (great little used bookstore),Cortez where I once unexpectedly had the best fried oysters I have ever eaten, through Monument Valley to Flagstaff.

Back through Seligman (no visible changes) and Kingman again with a stop at the Route 66 Distillery, then to Oatman where donkeys wander the streets and the 9-2-8 proves its fettle on tiny dirt roads. Then to LA and Monterey Park where you get the best Chinese food in North America. And home.

A warning: having to give up this car causes pain, suffering, and real feelings of deprivation. If it doesn’t, you didn’t belong in it in the first place.

The late Len Frank was the legendary co-host of “The Car Show”—the first and longest-running automotive broadcast program on the airwaves. Len was also a highly regarded journalist, having served in editorial roles with Motor Trend, Sports Car Graphic, Popular Mechanics, and a number of other publications. LA Car is proud to once again host “Look Down the Road – The Writings of Len Frank” within its pages. Special thanks to another long-time automotive journalist, Matt Stone, who has been serving as the curator of Len Frank’s archives after his passing in 1996 at the age of 60. During the next few months, we will be re-posting the entire collection of “Look Down the Road”, and you’ll be able to view them all in one location under the simple search term “Len Frank”. – Roy Nakano