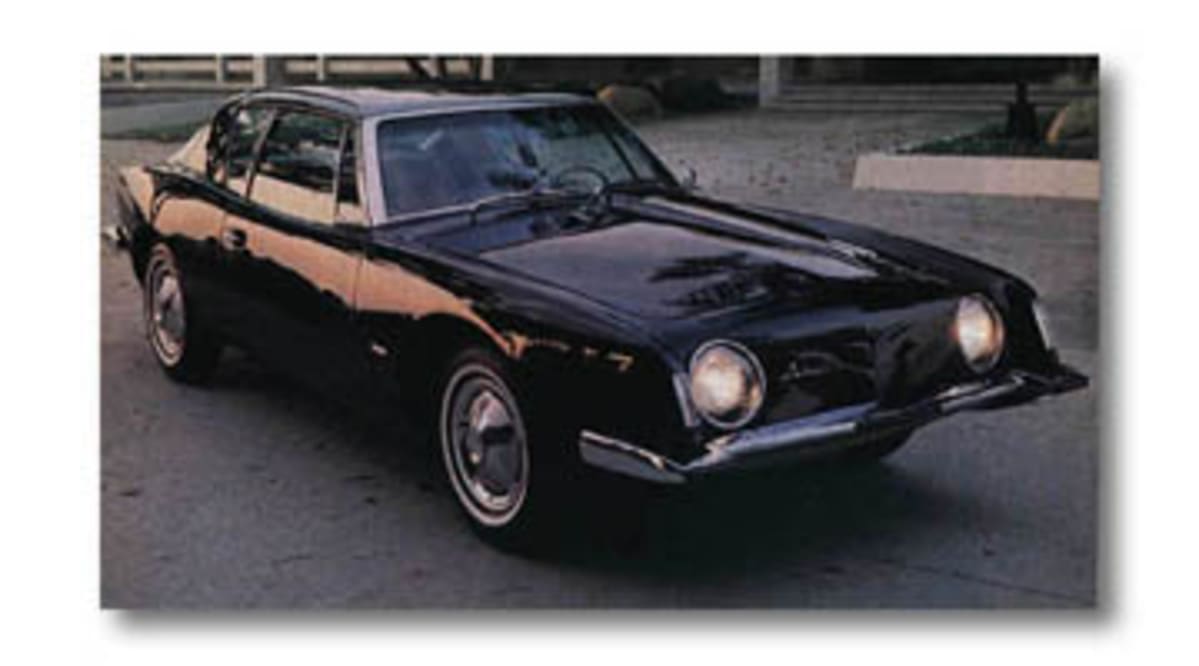

1963 Studebaker Avanti R2

Published on Mon, Feb 1, 1982

By: Len Frank

Len Frank on the car that even Studebaker couldn’t kill, as first published in Motor Trend, February, 1982

Let us consider the following: Studebaker, Raymond Loewy, Sherwood Egbert, the Avanti; a corporation, two people, and a car. Elements that just do not exist singly in an enthusiast car magazine vacuum.

Simple enough to write about cars. Cars are a collection of numbers, hard-edged, defined. People are the opposite. And corporations are collections of people and hard-edged things rolled into an inextricable whole.

So, first, Studebaker. Everybody’s daddy came west in a Studebaker covered wagon. Conestogas, they were called. By the time Rutherford B. Hayes swore to uphold the constitution, Studebaker was the largest manufacturer of wheeled vehicles in the world.

In the mid-Twenties, Studebaker was as good a bet to join Henry and the General in the Big Three as were Walter P. Chrysler and his boys. Studebakers, the pride of South Bend, Indiana, were Good Value, Solid, Dependable, and even pretty fast. In the Thirties, for instance, they ran a team of stock-block Indy cars that were solid, dependable, etc.

The Studebaker lineup covered only the middle class, from lower to upper. The Erskine and the Rockne were two ill-starred attempts to compete with ford, Plymouth, and Chevrolet. The Studebaker dynamic leadership hitched up its suspenders, tightened its belt, and engaged Raymond Loewy to help produce the Champion, the last Studebaker begun from a clean start.

Loewy is an intensely interesting character. He likes to think of himself as the father of industrial design. He studied engineering, which led, somehow, to a career as a designer of lingerie. From there it was a skip to advertising, sales promotions, and the complete supervision of sales campaigns.

His first application of design principles to a machine was the streamlining of a small printing press. Then it was the streamlining of a large railroad locomotive. By the early Thirties, the dapper Mr. Loewy had discovered automobiles.

Using his own funds, he designed (insofar as we know) and had built an elegant Hupmobile, which he used to sell Hupp on a design program. A few successful years later, Studebaker bought Loewy, natty pinstriped suit, foulard tie, fresh boutonniere, and all. It was the beginning of a peculiar alliance.

As the story goes, that handsome Hupmobile was the last automotive task on which Mr. Loewy actually soiled his manicured hands. He was an excellent businessman, an excellent salesman, an excellent chooser of personnel. It was too much to ask him to do the actual design work. It was not too much to ask him to take the credit. Although, in fairness to Loewy, in the case of failures – and there were some – he would also take the blame.

The ’39 Champion was well designed, clean, well received. So was the President Skyway. Both were largely unchanged through 1946. In mid-1946, the ’47 New Look was introduced and Loewy’s name was known throughout the land.

This was the car that looked essentially the same coming or going, easy fodder for comedians, and we never stopped laughing for some reason. Only years later did we learn that the car was really the work of Virgil Exner (Chrysler’s man of the Fifties – fins and all that – and designer of the gauche Stutz) who also didn’t get credit for the Karmann Ghia. Another story.

Exner was working for Loewy and independently for Studebaker, a kind of designing double agent. It was his independent design that became the revolutionary ’47. Whereupon Loewy fired Exner and managed to get the design attributed to himself. Loewy’s group was responsible for the Next Look (’50 and ’51). The original short hood/fenders were stretched into three separate nacelles that looked as if they had been picked up war surplus. Mr. Loewy was so amused that he appended a shiny chrome propeller to his personal car.

In the next few years, Studebaker acquired and promptly buried Packard, and then decided that the auto business was better left to others. The only automotive bright spot was the 1959 Lark – not a Loewy project – that brought in a profit of nearly $30 million. The executive responsible for the Lark (and its profit) was president Harold Churchill. So the board fired him.

Enter Sherwood Egbert at about double Churchill’s salary. Egbert was the charger who had saved McCulloch. Once a manufacturer of small two-strokes and automotive products (the McCulloch ne Paxton supercharger), McCulloch’s management had found fame and fortune by selling off its nasty hard-parts divisions and acquiring miles of empty desert land, filling same with water, and ultimately putting London Bridge on it. It all looked good to Studebaker.

What the Study big guys hadn’t counted on was that Egbert was a closet car freak. What is there about cars? There is no real evidence that at any time prior to his appearance at Studebaker Egbert had ever tumbled for a car. He hadn’t arrived for his interview in a Jaguar or a Ferrari. Or even a 4-passenger T-Bird. But by the time he was in the president’s chair, he was already doodling on the backs of envelopes. This while he simultaneously juggled Studebaker problems – cash flow, recalcitrant board members, loyal but lackluster dealers, obsolete product line, sharply increased domestic competition, and objections for a captive Mercedes-Benz, to name just a few.

Loewy was doing well for himself. He had designed office in Europe and the U.S. He had contracts with corporations and governments. He was the world’’ best known industrial designer. Every morning he had a fresh boutonniere.

Raymond Loewy had had a long succession of personal cars that featured the “Loewy look” of the time. There was that rakish Hupmobile touring car with cycle fenders; a prewar Lincoln Continental demoralized by portholes and a grille of concentric circles pasted on its once patrician nose; a BMW 507 (by the man who later did most of the 240Z, Albrecht Goertz), with a Loewy-designed body of surpassing ugliness: a “gun sight” asymmetrically mounted on the hood, swooping fenders, pinched waist, a bulbous, glassy tail; a Jaguar with a variation on that look made even more difficult by the high engine; and the granddaddy of them all, the Loraymo. This was the model, on a Lancia chassis, for the persistent styling theme that Loewy later used on the DMW and Jaguar. The bulbous rear was even more clumsily handled, the Italian coach builder having had problems with both shape and method of construction. On the hood was the genesis of asymmetry. The outsized grille was flanked by cutaway flying fenders and headlights on stalks reminiscent of the eyes of a hammerhead shark.

So Egbert got hold of Loewy and on March 9, 1961, asked if Loewy might have a design in two weeks. Egbert also have Loewy a bunch of clippings he had been cutting out of car magazines for months. Loewy, since his function had little to do with design, could see no reason why a design could not be ready in two weeks.

Loewy borrowed a house on the edge of Palm Springs, California, and installed a team of three: John Ebstein, to supervise along with Loewy; Bob Andrews, who had worked on the ’48 “step-down” Hudson as a designer and clay modeler; and Tom Kellogg, five years out of Art Center. Raymond Loewy and wife, properly attired in desert togs, dropped by from time to time to boost morale, make suggestions. Ebstein supervised, Kellogg designed, Andrews incorporated the designs into a one-eighth-scale model.

Loewy had supplied, along with Egbert’s clippings, pictures of his BMW, Jag, and, God help us, the Loraymo. Using these as “inspiration” (see the asymmetrical hood device, “Coke-bottle shape,” bulbous tail . . .) the team produced – in two weeks – a completed model. Reams of Kellogg’s sketches showing interior and exterior details were rushed back to South Bend where Gene Hardig, Studebaker’s long-suffering chief engineer (build us a new car, Gene, but don’t spend any money doing it . . .”), had the job of turning the clay into a car.

Meanwhile, Sherwood Egbert somehow talked the hidebound board of directors into the project. How he convinced them that the best way out of the automobile business was to build an irresistible new car is a great mystery. Attribute it to Egbert’s personal horsepower.

Kellogg remembers it as a time of high enthusiasm, of camaraderie, creativity, excitement. He had become a designer, he says, because he was inspired by Loewy’s (Exner’s) ’47 New Look car. The chance to work for Loewy was a dream realized.

Too often a dream car is turned into a nightmare by those of little courage and less taste. The Avanti was spared. Hardig insisted it a 4-seater. Robert Doegler axed the fender flared in building the full-sized clay, Egbert had the tail shortened and the windshield slope decreased. One nice detail that was dropped was exposed fuel filler and spare tire a la various Ferrari coupes.

Hardig performed miracles in getting the old Lark convertible chassis up to standard: The 232-cu.-in. 1951 V-8 was stretched to 289, newly acquired Paxton division supplied a supercharger, Bendix supplied Dunlop patent disc brakes, Borg-Warner a modified automatic and an optional 4-speed. It was ready, despite a UAW strike, by April 1962, for the New York International Auto show. It was a smash.

But the downward momentum of the years was too much, Andy Granatelli and his trenchcoat, a package deal along with Paxton, set about record breaking to give the car a performance image. One car, after setting four different coast-to-coast records, was driven 147 mph with three passengers, using the same engine and Sears tires as on the cross-country runs. Another car, the modified “Due Centro” with the only R-5 dual-supercharged engine built by Paxton, went 196.62. It didn’t matter.

Production difficulties and the Studebaker board killed the Avanti – at least as far as Studebaker was concerned. Worn out and sick, Sherwood Egbert went on leave of absence in October 1963. In November, the board appointed a new president. In December, the cessation of production in south Bend was announced. The Avanti and the Hawk were first to go. Lark production dribbled on in Canada (with Chevy engines) until spring of 1966. Sherwood H. Egbert died in 1969.

The Avanti shown here is something a pampered lady. It belongs to Wendell Hanks, a teacher of speech and speech therapy at a Southern California community college, and has, in its turn, provided its owner with a bit of therapy. There is also the possibility that the therapy might no have been needed had it not been for the Avanti.

Hanks is the second owner. The first, an elderly gentleman from the desert burg of Saugus, California, sold the car to spare it from the less-than-tender ministrations of his sons. That was at 22,000 miles in 1964.

Now, 80,000 miles later, the engine has been rebuilt once (at 70,000 miles), the car has been repainted three times (gold, gold, black), and the seats have been reupholstered once. Hanks took classes in auto restoration and did the prep, but he finally hired the instructor to do the actual painting.

Mr. Hanks does not drive his car much now because of the fragility of the restoration, but he says anyway “. . . it is an art work to me . . . a piece of sculpture . . . and you can’t keep a Rodin in the garage.”

Avanti II

Nate Altman and Leo Newman were Packard, Studebaker, Edsel dealers in South Bend who could learn from experience.

Altman decided that the now-scratched Avanti was just what was needed to grace his showroom floor. He approached Morris Markin, president of Checker, to see about taking over Avanti production. Markin thought the Avanti an “ugly” car. Exit Checker.

Capitalizing on his own business acumen, Altman was able to secure at favorable prices the old Avanti assembly plant, all the Avanti tooling, body production form Molded Fiberglas (manufactures of the Corvette body panels), necessary credit, and the continued employment of Gene Hardig.

Hardig began by switching the Chevy power (first a 327, then a 400, now a 305) and modifying the body by eliminating the rake and raising the front fender line.

The best of the Studebaker employees were kept; car production was nominally set at 300 per year, with quality the major criterion. The chassis has been modernized as necessary by using readily available Chevy components.

Nate Altman died in 1976, but his brother and Newman and Gene Hardig are still there. The car has become much more a gentleman’s personal transport than the semi-ripsnorter Egbert had in mind originally.

A quick check with the local dealer. Ricker Motors of Los Angeles, California, an old-time Studebaker dealer (now AMC/Renault, Avanti), showed two in stock at a nicely equipped base price of $22,995. This includes Avanti’s traditional roll bar, all power equipment, THM 3580 trans, sound systems, etc. If you like, Recaros, suede, leather, even a chrome-plated boat-trailer hitch are available.

It must be the least expensive hand-built comprehensive car left.

Top image: 1963 Studebaker Avanti advertisement photograh (public domain)

The late Len Frank was the legendary co-host of “The Car Show”—the first and longest-running automotive broadcast program on the airwaves. Len was also a highly regarded journalist, having served in editorial roles with Motor Trend, Sports Car Graphic, Popular Mechanics, and a number of other publications. LA Car is proud to once again host “Look Down the Road – The Writings of Len Frank” within its pages. Special thanks to another long-time automotive journalist, Matt Stone, who has been serving as the curator of Len Frank’s archives since his passing in 1996. Now, you’ll be able to view them all in one location under the simple search term “Len Frank”, or just click this link: Look Down The Road. – Roy Nakano